As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread across the world, clinicians, academic institutions, private organizations, and governments are working tirelessly to find treatments to help patients and at-risk populations threatened by this novel disease. The best minds in infectious disease and immunology are focusing on mechanisms for future therapies that are both safe and effective. In the absence of approved therapies, some investigators are looking towards drug products indicated for other conditions with the goal of repurposing them for COVID-19 indications. This means investigating a previously approved therapeutic as a potential therapy for an entirely new indication, in this case, COVID-19. Repurposing of an approved therapy allows for expedited access to clinical trial approval, accelerating the regulatory approval process. And the approval rate for a repurposed therapy is approximately 30% better than for a novel drug.

Ototoxicity of several investigational treatments for COVID-19

Potential repurposed treatments include antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and antimalarial drugs, among others. All of the aforementioned treatments require appropriate drug development processes, including clinical trials on patients with COVID-19 to evaluate the risk-benefit balance of these compounds. As of the beginning of July 2020, more than 1,300 clinical trials for COVID-19 treatments have been registered worldwide, giving hope to patients and promising a significant competitive advantage to the pharmaceutical companies pursuing these trials.

Some of the drugs that are currently under investigation present off-target risks, including ototoxicity. The effects of ototoxicity can be transient, or can be irreversible and permanent. Ototoxicity and associated auditory pathologies affect millions of patients, contributing to a diminished quality of life. More troubling is that hearing loss is associated with an increased risk of dementia, anxiety, hospitalizations, and overall increased mortality. Early assessments of auditory safety for potential COVID-19 therapies are essential to defining a minimum effective therapeutic dose for the potential treatment while still maintaining appropriate safety parameters.

For example, in March 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted an emergency use authorization (EUA) to allow the emergency use of hydroxychloroquine sulfate for COVID-19 treatment in controlled clinical trials. However, this EUA was revoked in June 2020. In addition to the documented retinal toxicity, chloroquine and its analogs are chemically similar to quinine, which is known to cause temporary ototoxicity resulting in tinnitus. Quinine products can also temporarily reduce balance, implicating vestibular cochlear toxicity. Preclinical testing for auditory safety can mitigate clinical complications that may arise from ototoxicity, especially if it is irreversible.

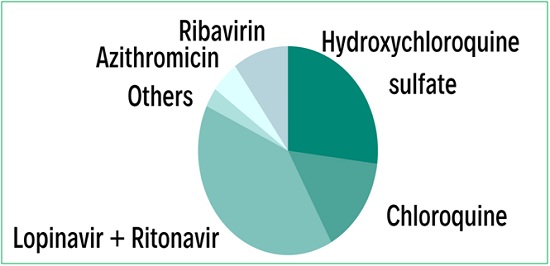

Figure 1. Relative reported ototoxicity of current investigational treatments for COVID-19. Azithromycin is a macrolide antibiotic used to treat common infections of the respiratory system, the ear, and the eye. Macrolides, including azithromycin, clarithromycin, and erythromycin have all been reported to present ototoxic effects.

Why do we need to test for auditory safety?

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) data, in 2018, an estimated 466 million people around the world suffered from disabling hearing loss; that number is expected to reach 900 million by 2050. Hearing impairment is the most frequent sensory deficit in human populations, with most individuals suffering from disabling hearing loss residing in low- and middle-income countries that lack access to appropriate care such as hearing aids. Hearing loss impedes the ability to communicate, adversely impacting access to education, employment, parenting, and personal safety. In developing countries, the schooling rate among children with hearing loss is significantly lower than among children with unimpaired hearing, while the unemployment rate of adults with hearing disabilities is much higher. Overall, it has been shown that preventive measures for hearing loss are cost-effective and can bring great benefit to individuals and communities.

Most of the data regarding the ototoxic effects of approved drugs comes from the post-marketing reports of Phase Four clinical studies when potentially irreversible hearing damage has already occurred. Preclinical testing for auditory safety allows the assessment of potential ototoxicity properties earlier in the drug development process and helps to avoid potential clinical and financial risks as the drug enters the market. Since all drugs are evaluated based on their risk-benefit ratio, decreasing the risk by addressing ototoxicity early improves the chances of approval.

The aim of a preclinical ototoxicity testing

A preclinical ototoxicity study aims to screen the investigational product for auditory safety. Since several formulations may be tested simultaneously, the optimal non-ototoxic dose can be selected for further trials. Finally, if there are several similar compounds with comparable therapeutic profiles, like hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, it is easy to visualize the range of off-target adverse events.

A preclinical ototoxicity study aims to screen the investigational product for auditory safety. Since several formulations may be tested simultaneously, the optimal non-ototoxic dose can be selected for further trials. Finally, if there are several similar compounds with comparable therapeutic profiles, like hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, it is easy to visualize the range of off-target adverse events.

CILcare/CBSET ototoxicity screening models (GLP and non-GLP ototoxicity testing)

Non-clinical studies can provide evidence of a positive risk-benefit ratio prior to human administration. The auditory specialists at CILcare and CBSET screen potentially ototoxic compounds through:

A. In vitro culture of the organ of Corti with otic cell line: a high-throughput assay to screen a large number of therapeutic compounds.

B. Ex vivo studies on cochlear explants: an excellent model to study the effect of a drug candidate on various cochlear cell types. Cochlear explant studies allow quantification of cellular populations, structures, and functional subunits such as synapses.

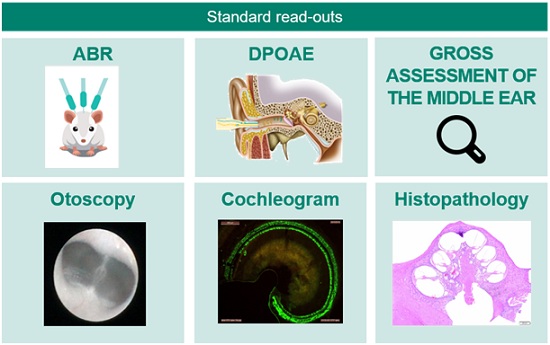

C. In vivo studies: These studies are supplemented by several complementary readouts (Figure 2) designed to assess the potential ototoxicity of therapeutics in relevant species using functional, physiological, and morphological readouts.

Figure 2. CILcare/CBSET’s in vivo models allow the rapid testing of ototoxicity using functional, physiological, and morphological readouts.

The main readouts for ototoxicity studies include:

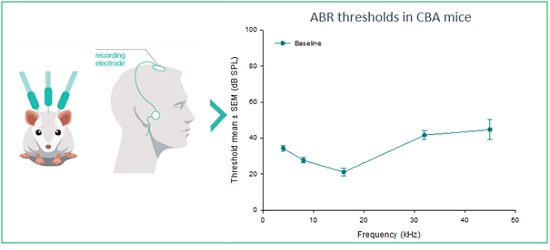

- Auditory Brainstem Responses (ABRs) to assess the activity and integrity of the inner hair cells and the auditory nerve.

- Distortion Product Otoacoustic Emissions (DPOAEs) to detect the activity of the outer hair cells.

- Wave I analysis to assess synaptic function.

- Histopathology with hair cells & ribbon synapse counts to evaluate cochlear damage.

Figure 3. Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) measurements are electric potentials recorded from scalp electrodes. This non-invasive translational method enables the determination of auditory response thresholds.

Meeting regulatory guidelines

CILcare and CBSET have created a strategic alliance to provide developers of drugs, gene therapies, cell therapies, and medical devices with cutting-edge preclinical services for the evaluation of auditory functions and safety in a regulated GLP environment.

FDA guidance documents specify auditory safety evaluation utilizing two methodologies: in vivo assessment (historically, ABR measurements) and ex vivo assessment (cochleograms). CILcare and CBSET experts use state-of-the-art acoustic and electrophysiology equipment, as well as high throughput and excellent technical skills, to ensure accurate and reproducible ABR measurements. Cytocochleograms enable the histopathological assessment of ototoxic damage on the inner and outer hair cells of the cochlea, with anatomical localization corresponding to predicable patterns of functional deficits. Extensive training ensures that cochlea preparation is performed with minimal artefacting. Sophisticated microscopy delivers high-quality imaging for the accurate quantification of hair cell density and distribution. State-of-the-art technology enables automated quantification, delivering rapid and accurate readouts efficiently.

Conclusion

While it is crucial to find effective treatments for COVID-19, the safety of potential treatments needs to be assessed early in the drug development process to avoid unnecessary risks. Ototoxicity of potential COVID-19 treatments is probable based on existing data on the drug classes under consideration, and therefore should not be neglected. Damage to the auditory system due to drug exposure may result in transient or irreversible hearing disorders, such as hearing loss, hyperacusis, and tinnitus, as well as an overall deterioration in quality of life. Imagine if we could treat patients for COVID-19 while preserving this precious sense, HEARING!

Author: Michael Naimark

Michael Naimark is Director of Business Development at CBSET Inc., a GLP-compliant preclinical translational research institute located in Lexington, Massachusetts. Following a career as a preclinical study director and project manager, Michael focuses on client-centered outreach in developing new services and capabilities. He holds an MS degree in neurobiology from the University of Tennessee Medical Center and is a co-author of several peer-reviewed publications with an emphasis on stem cell biology and retinal physiology.

Michael Naimark is Director of Business Development at CBSET Inc., a GLP-compliant preclinical translational research institute located in Lexington, Massachusetts. Following a career as a preclinical study director and project manager, Michael focuses on client-centered outreach in developing new services and capabilities. He holds an MS degree in neurobiology from the University of Tennessee Medical Center and is a co-author of several peer-reviewed publications with an emphasis on stem cell biology and retinal physiology.